Authors: Elena Volodina, Yousuf Ali Mohammed, Therese Lindström Tiedemann

In our previous blog on the Swedish Word Family we described how morphologically annotated resources can be used for analysis of texts for cultural aspects, namely, how different holidays are represented in second language corpora.

Today, we would like to showcase how the same Word Family resource (under the Morphological profile in Swedish L2 profiles) can be used to study several hypotheses connected to learner language, namely:

- Simpler words (consisting of a minimal number of morphemes) within each family appear at earlier levels and are more frequent.

- Related to the above: relations between word family members are ordered by complexity through word formation mechanisms (cf. Lango et al. (2021)) which is reflected in the order of appearance of the new word family items in receptive and productive data. (We simplify the notion of complexity and assume here that the higher number of morphemes per word indicates a more ‘complex’ word.)

To look into these hypotheses, we start from an analysis of the distribution of distinct simplex root lexemes in the two corpora. By simplex root lexeme we understand lexical items that consist strictly of one root only, e.g. dag (‘day’). By being distinct we mean that we account for each simplex root lexeme only once, at the level where they occur for the first time. For example, dag is used for the first time at A1-level, but is repeatedly used at all other levels. We count dag only once, at the level of its first occurrence. (We, thus, do not count dag among simplex root lexemes at levels above.)

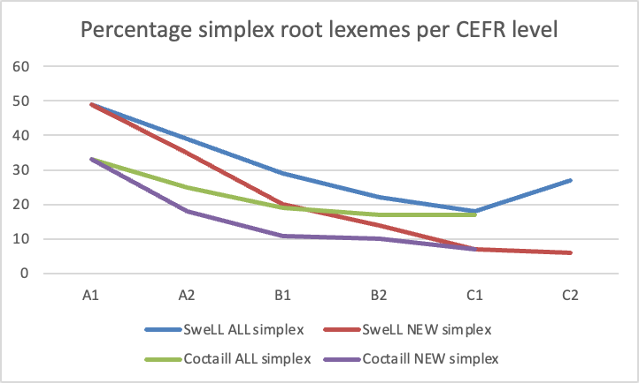

There are 2298 distinct simplex root lexemes in total in the Swedish Word Family resource. These are split between receptive (2195 items) and productive (1108 items) corpora, with an overlap of 1063 items. The figure below convincingly shows that simplex root lexemes are more represented among new vocabulary items at earlier levels and gradually decline as proficiency grows, even though we can see that this effect levels off in the receptive data from B1-level, both regarding all simplex root lexemes and when only taking the new ones into account. In the productive data there are generally more simplex roots than in the receptive data (see Fig.1), probably indicating that they are easier to learn to use.

Figure 1. Distribution of simplex root lexemes over the two corpora: course books and learner essays. The Y-axis represents the percentage of root lexemes: ALL = relative to all items at that level; NEW = relative to all new items at that level.

At A1-level in learner essays half of the new vocabulary consists of lexemes with only a root morpheme. By C1-level, this drops to 7%. The same tendency can be seen in the course book corpus: at A1-level, 33% of all lexical items are simplex root lexemes, whereas by C1 the percentage of new simplex root lexemes drops to 7%. There is an increase on C2-level for productive simplex root lexemes, however this may be partly due to the small data size.

An interesting question is whether simplex root lexemes within their respective word families tend to precede items that are more complex in terms of word formation (derivations and compounds). That is, whether learners first get acquainted with, for example, the simplex root lexeme dag, and then learn its derivations (e.g. daglig ‘daily’, dagis ‘daycare/kindergarten’) and compounds (e.g. måndag ‘Monday’, vårdag ‘Spring day’). We have looked into several word families to examine this assumption, namely

- the dag-family (sharing the root dag ‘day’)

- the språk-family (sharing the root språk ‘language’)

- the lyx-family (sharing the root lyx ‘luxury’)

To do that, for each word family we have examined all their family members and their distribution per level in the two learner corpora, COCTAILL (Volodina et al., 2014) and SweLL-pilot (Volodina et al., 2016), to figure out whether there are any particular patterns that could be of interest in a L2 learning context. We have experimented with different visualization techniques, to identify which ones best capture the different patterns within word families.

1. Morphological complexity within the dag-family (‘day’)

Figure 2. The dag-family in the receptive data (course books), new items per level.

The dag-family ‘day’ is one of the largest word families in the Swedish Word Family resource with a total of 101 members in the Coctaill corpus, 32 of which are also represented in the learner essays in the SweLL-pilot corpus. As hypothesized, the simplex item consisting of only the root, dag, is introduced before other items, at A1-level, together with some derivatives and compounds, namely days of the week (lördag ‘Saturday’, fredag ‘Friday’, etc.) and some of the words describing everyday routines, such as middag ‘dinner’, dagis ‘daycare/kindergarten’, as well as parts of the day, eftermiddag ‘afternoon’. It is obvious from the word cloud in Figure 2 that the root lexeme dag ‘day’ is by far the most frequent in the dag-family at A1-level.

While members of the dag-family at A1-level reveal that the central topics at that level are focused around the daily needs and routines, the dag-family members at A2 suggest that texts which learners read focus on two distinct topics: society and festivities. Societal words are represented by such members as dagstidning ‘daily newspaper’, riksdag ‘parliament’, and a few compounds with riksdag, e.g. riksdagsparti ‘parliamentary party’, riksdagsval ‘parliamentary election’ and relate well to the fact that at this CEFR-level learners are expected to learn to communicate more about society around them. The topic of holidays and festivities is represented by a whole range of words, with such members as nationaldag* ‘national day’, allhelgonadag* ‘All Saint’s day’, nyårsdag(en)* ‘New Year’s day’, with the most prominent family member being födelsedag ‘birthday’.

At the next levels, we see that the dag-family is growing through numerous complex patterns of compounding and derivation, with up to five roots within one item, e.g. här-om-dag-en (3 roots; ‘the other day’), sön-dag-s-efter-mid-dag (5 roots; ‘Sunday afternoon’). Interestingly, most family members are nouns, with only few adjectives (daglig ‘daily’, gammaldags ‘old fashioned’), adverbs (dagligen ‘on a daily basis’, häromdagen ‘the other day’) and proper names, of which both designate names of newspapers (Dagens nyheter, Svenska Dagbladet); and there are no verbs apart from the multi-word expression sova middag ‘have an afternoon nap’.

One more interesting observation is that the most radical expansion of the family happens at A2 and B1 levels, fewer and fewer new items appearing after these two levels, with as little as only seven new items at C1 level. This is most probably due to the “topical” nature of the word dag and the fact that daily routines have already been well covered at earlier levels.

2. Morphological complexity within the språk-family (‘language’)

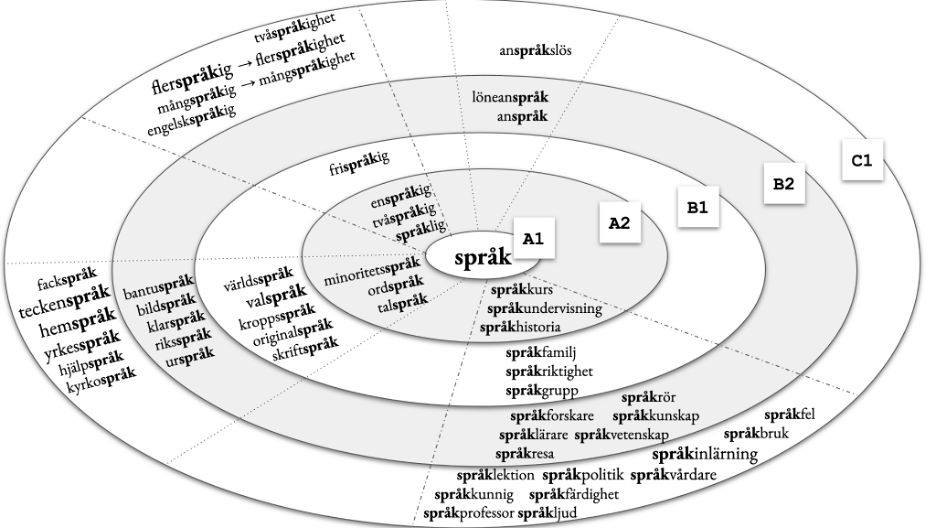

Figure 3. Distribution of the språk-family ‘language’ in the receptive data.

A predictable pattern of “easy first” can be traced also in the språk-family, exhibiting 62 family members, with 57 of them appearing in the Coctaill corpus (i.e. in course book texts). The root lexeme språk ‘language’ appears first at A1-level in both corpora and is the only representative of the family at that level (see the center of Figure 3). We can assume that its presence in the texts has a priming effect on learners, making it possible to combine that root with a number of other roots and affixes at the higher levels.

There are a few distinct patterns that we observe in the språk-family development across levels (also visualized in Figure 3):

- (numeral/adjective root) + språk + adjectival suffix -ig, e.g. enspråkig ‘monolingual’, frispråkig ‘outspoken’, flerspråkig ‘multilingual’ → in turn, leading to a derivation pattern with the nominalising suffix -het at the advanced levels, e.g. flerspråkighet ‘multilinguality’.

- compound nouns, ending in språk, that describe various types of languages, e.g. talspråk ‘spoken language’, riksspråk ‘national language’, yrkesspråk ‘professional language’. The left hand element is usually a noun used as a modifier. This seems to be one of the most productive patterns of word formation within this word family.

- språk used as a left-hand element in compounds to modify other nouns, e.g. språkkurs ‘language course’, språkfamilj ‘language family’, språkpolitik ‘language politics’. This pattern of word formation is highly productive, making the word family expand vastly by the C1-level, see Figure 3.

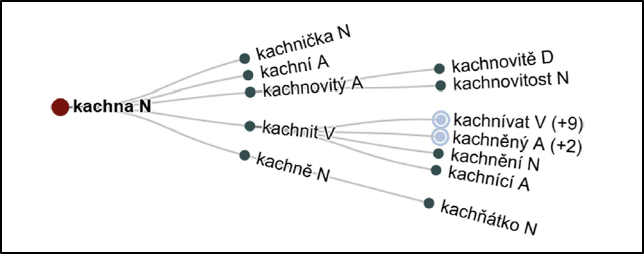

The outlined tendencies observed in course books echo analysis of the word formation networks in Czech and other languages, a representation of one of them shown in Figure 4 based on Lango et al. (2021). While Lango et al. (2021) aimed at a general language description and analysis, we see similar patterns in the learner language. A hypothesis that more complex patterns follow easier patterns requires, however, more thorough examination of a far larger number of word families than we provide here, correlating those with each other and with morphological families, i.e. families in a broader sense, where lexical items are centered around a shared affix or root, and listed with frequencies of the morphemes and other linguistic variables.

Figure 4. A word formation network for Czech. A reprint from Lango et al. (2021).

All in all, the above analysis of the språk-family demonstrates a clear case where few word-formation patterns give rise to several new lexical items. Notably, most of the språk-family members are used very infrequently with few exceptions, such as flerspråkig ‘multilingual’, hemspråk ‘home language’, cf. ‘heritage language’ and teckenspråk ‘sign language’, all of which appear at C1-level. The core item itself, språk, dominates at all levels, not only at the level of first occurrence; which is probably easily explainable by the course orientation.

3. Morphological complexity within the lyx-family (‘luxury’)

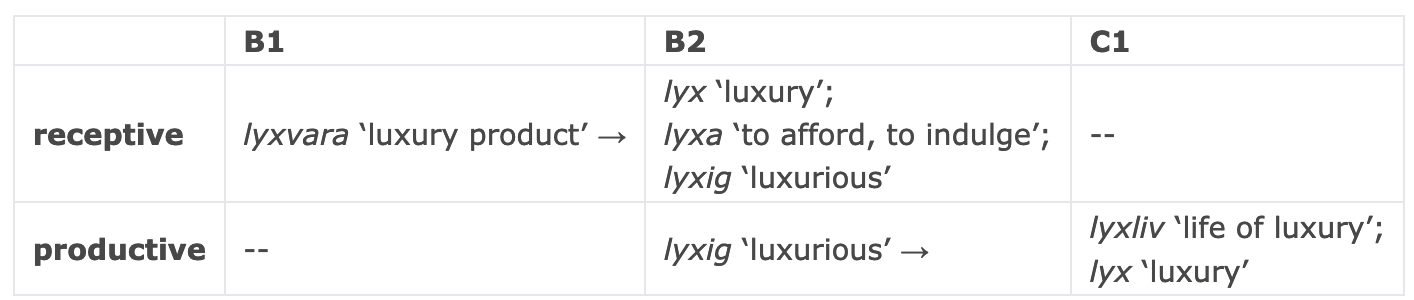

Most families we have looked into seem to follow the path outlined above, i.e. introducing simpler words before more complex ones. However, an important step when examining a hypothesis is to find counterexamples that could trigger new insights. One such counterexample is represented by the lyx-family ‘luxury’. It contains only 5 members, distributed in the data as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. The lyx-family (‘luxury’).

A more intuitive order of introduction, following the principle of ‘easy first’, would be:

lyx → lyxa, lyxig, lyxliv, lyxvara

However, we can see that the order of appearance of the words in the lyx-family is counter-intuitive: a compound lyxvara ‘luxury item’ appears before the simplex root item lyx ‘luxury’ and its derivatives lyxig ‘luxurious’ and lyxa ‘to indulge, to treat yourself to luxury’. Several explanations come to mind, apart from the obvious one that natural languages are idiosyncratic, and do not tend to adhere to rules:

The first one is connected to the reasoning about ‘what makes an item easy’. Up to now we operated under the assumption that the simplest morphological structure is the main distinctive feature of an easy item. This is, of course, a simplified view on reality. To complicate this, semantics could be another constituent of the “simplicity equation” that needs to be considered, in this case, the dichotomy between the concreteness and the abstractness of the words in the lyx-family. All of the lyx-items at B2-level have an abstract meaning whereas the B1 item lyxvara is concrete. From the cognitive point of view it may be easier to acquire a concrete item (lyxvara) than more abstract ones.** Future research should investigate the relation between vocabulary acquisition in L2 and abstractness and concreteness.

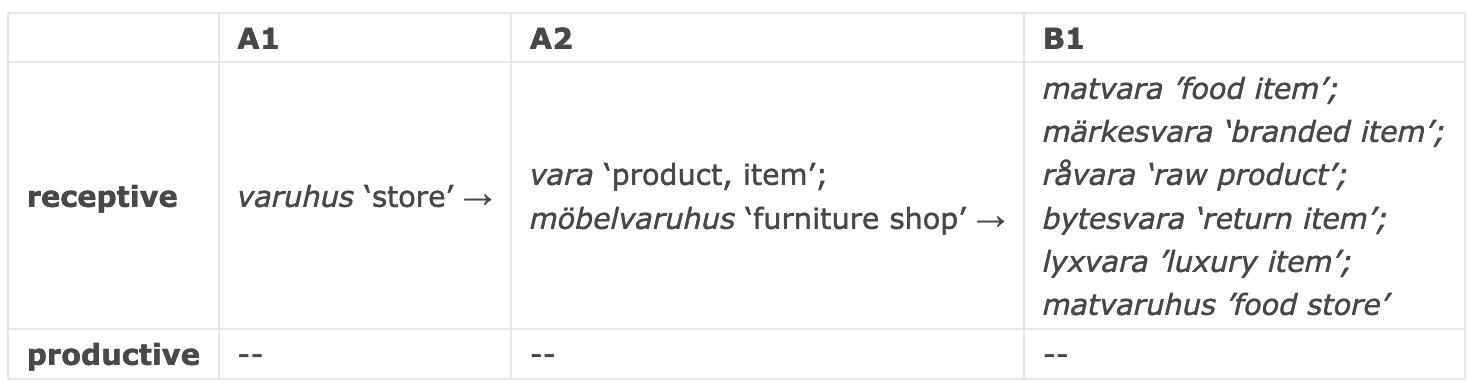

The second likely explanation could be the priming effect of the second family that lyxvara belongs to, namely the var-family. If we examine how vara ‘product, item’ is used in coursebooks (Coctaill), we will see that up to B1 ten (10) family members are introduced, as shown in Table 2, and all of them are compounds except the root itself (vara, ‘product, item’). Shopping seems to be one of the central topics in texts at B1-level, since various types of products are introduced. The word formation pattern is very similar between five of the six items containing the root var at B1-level: ‘a modifier describing the type of product + vara’; lyxvara falls into this pattern, and becomes the first member of the lyx-family to get introduced to language learners. It is possible to speak about a priming effect of statistically recursive orthographic chunks (in this case ‘modifier+vara’), which, after repeated appearances, start to distinguish themselves as separate morphemes: i.e. vara as a separate item, distinct from a range of modifiers, and gradually, lyx also becomes recognized as an independent lexical item.

Table 2. An excerpt of var(a)-family. In the productive data, the noun vara (‘product, item’) appears at B2 level for the first time and is therefore outside this Table.

Interestingly, even in the case of the var-family, we see that the first item introduced at A1-level is not the root item vara, but the compound varuhus ‘store’ (literally ‘house/building with goods’), see Table 2. It would make sense to check the pattern of introduction of the hus-family members, and there is good reason to believe that this would lead to another quest and become a “never-ending story”. Besides, the topical focus of texts influence which items that are introduced at which levels, which is a predictable consequence of sequencing language education: learners first need to learn how to introduce themself and attend to their immediate needs, and gradually to lift their attention to the world around them and topics that are no longer centered on learners. The hus-family and the var-family are two clear examples of how central topics change over the proficiency levels in relation to learner needs, as we also see in the CEFR level can-do statements (COE, 2020).

Finally, hypothetically there are good reasons why most word family resources do not include compounds: compounds add factors that are difficult to account for, such as exposure to the “other” families and influence thereof, and since word families are often used in relation to frequency bands, compounds would be complicated to include in the total frequency counts since they can combine a high-frequency and a low-frequency word family. If we disregard the compounds in the lyx-family, the pattern in our other two examples would be the “simplex first”, and all words in the family would be linked to the same level as the morphologically simplest one among them (see Table 1, B2-level). Compounds are debated in cognitive research on morphology, some studies positing that compounds are processed as whole-word units, whereas others show evidence that access to constituent morphemes prior to the whole compound word facilitates mental access to the item, see a review of studies in Leminen et al. (2019). Regardless, the suggestion to remove compounds from the analysis of word families is not viable for Swedish, since compounding is the most widely spread word formation mechanism (cf. Svensson, 2022) and many new roots are learnt initially from compounds, like var(a) from varuhus and lyx from lyxvara. In fact, even proper names which are made up of compounds have been recognised to help L2 Swedish learners learn new roots, such as torg ‘square’ from place names like Opaltorget (Löfdahl, Tingsell & Wenner, 2015). Swedish proper names quite often contain roots which learners are exposed to as separate root lexemes only after they have encountered them in place names (Lindström Tiedemann, 2023).

To summarize, we have traced the learning order of the word lyx as follows:

- hus (A1) → varuhus (A1) → vara (A2) → lyxvara (B1) → lyx (B2)

* The holidays allhelgonadagen and nyårsdagen usually appear in the definite form, however dictionaries tend to list them in the indefinite form (allhelgonadag, nyårsdag) (see e.g. https://svenska.se) and the same is true in our resource.

** cf. differences in processability (Binder et al, 2005) and recognition (Fliessbach et al, 2006). Some research has shown that children tend to know mainly concrete words at first, followed by a sharp increase in abstract vocabulary (Ponari, Norbury & Vigliocco, 2018)

This blog is based on Volodina, Mohammed and Lindström Tiedemann (2022).

References

- Binder, J.R., Westbury, C.F., McKiernan, K.A., Possing, E.T., & Medler, D.A. (2005). Distinct Brain Systems for Processing Concrete and Abstract Concepts. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 17(6), 905–917.

- Council of Europe [COE]. (2020). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: learning, teaching, assessment: companion volume. Council of Europe Publishing.

- Fliessbach, K., Weis, S., Klaver, P., Elger, C. E., & Weber, B. (2006). The effect of word concreteness on recognition memory. NeuroImage (Orlando, Fla.), 32(3), 1413–1421.

- Lango, Mateusz, Žabokrtský, Zdeněk, & Ševčíková, Magda. (2021). Semi-automatic construction of word-formation networks. Language Resources and Evaluation, 55(1), 3-32.

- Leminen, Alina, Smolka, Eva, Dunabeitia, Jon A., & Pliatsikas, Christos. (2019). Morphological processing in the brain: The good (inflection), the bad (derivation) and the ugly (compounding). Cortex, 116, 4-44.

- Lindström Tiedemann, Therese. (2023). Egennamn, morfologi och andraspråksinlärning [=Proper names, morphology and second language acquisition]. In: Väinö Syrjälä, Terhi Ainiala, Pamela Gustavsson (eds.) Namn och gränser: Rapport från den sjuttonde nordiska namnforskarkongressen den 8–11 June 2021. Uppsala. Pp. 223–250.

- Löfdahl, Maria, Tingsell, Sofia, & Wenner, Lena. (2015). Lexikon, onomastikon och flerspråkighet [= Lexicon, onomasticon and multilingualism]. In: E. Aldrin, L. Gustafsson, M. Löfdahl & L. Wenner (eds.) Innovationer i namn och namnmönster. pp. 153–167.

- Svensson, Anders. (2022). Tre av fyra nyord är substantiv [=Three out of four neologisms are nouns]. Språktidningen 2 Jan. 2022.

- Ponari, M., Norbury, C. F., & Vigliocco, G. (2018). Acquisition of abstract concepts is influenced by emotional valence. Developmental science, 21(2), pp.1-12.

- Elena Volodina, Yousuf Ali Mohammed and Therese Lindström Tiedemann. (2022). Lyxig språklig födelsedagspresent from the Swedish Word Family. In Volodina, Dannélls, Berdicevskis, Forsberg and Virk (editors), Live and Learn – Festschrift in honor of Lars Borin, pages 153–160. Available under CC BY 4.0

- Volodina, Elena, Pilán, Ildikó, Rødven Eide, Stian, & Heidarsson, Hannes. (2014). You get what you annotate: a pedagogically annotated corpus of coursebooks for Swedish as a Second Language. Proceedings of the third workshop on NLP for computer-assisted language learning. NEALT Proceedings Series 22 / Linköping Electronic Conference Proceedings 107: 128–144.

- Volodina, Elena, Pilán, Ildikó, Enström, Ingegerd, Llozhi, Lorena, Lundkvist, Peter, Sundberg, Gunlög, & Sandell, Monica. (2016). SweLL on the rise: Swedish Learner Language corpus for European Reference Level studies. Proceedings of LREC 2016, Slovenia.