Lars Borin, Anju Saxena, Shafqat Mumtaz Virk, Bernard Comrie

South Asia – comprising the seven countries Pakistan, India, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives, as well as immediately adjacent areas of neighboring countries (parts of Afghanistan, China, and Myanmar) – is the home of hundreds of languages belonging to several unrelated language families. The region has a long history of far-ranging multilingualism and close linguistic and cultural contacts, the details of which are still far from completely understood.

Today, the traditional (manual) linguistic way of investigating language genealogy, language contact, and language typology is being complemented by the introduction of large-scale computational methods. Such methods rely crucially on digital language data being available in large quantities and in appropriate formats, and the validity of their results is dependent on the quality of such data.

With this in mind, we have been pursuing the research project South Asia as a linguistic area? Exploring big-data methods in areal and genetic linguistics funded by the Swedish Research Council (grant no. VR dnr 421-2014-969), for the period 2015–2021 (see <https://spraakbanken.gu.se/en/projects/digital-lsi>). The members of the project team are Lars Borin (PI), Shafqat Mumtaz Virk (both Språkbanken Text, University of Gothenburg), Anju Saxena (Uppsala University), and Bernard Comrie (University of California, Santa Barbara). One of the aims of this project has been to make available in enriched digital form an extensive traditional source of information on the languages of South Asia, namely the Linguistic Survey of India (LSI; Grierson 1903–1927). As of 2019, the LSI is out of copyright and all of its content can consequently now be made freely available on the internet.

In this project, we are making the following LSI-based datasets available, all open-access and fully downloadable: (1) the full text of the LSI digitized and enriched with linguistic and text-metadata annotations; (2) a database of linguistic features for over 200 South Asian language varieties; and (3) a comparative vocabulary for close to 300 languages. (See below for details.)

The data source: Grierson’s and Konow’s Linguistic Survey of India

The linguistic richness and diversity of South Asia were documented by the British Indian administration in a large-scale survey conducted in the late nineteenth and the early twentieth century under the supervision of Sir George Abraham Grierson (1851–1941) and Sten Konow (1867–1948). The survey resulted in a massive detailed report comprising 11 volumes in 19 parts, around 9,500 pages in total, entitled Linguistic Survey of India (LSI); see <https://dsal.uchicago.edu/books/lsi/> for an overview of LSI. The survey covered 723 linguistic varieties representing the major language families of the region and some unclassified languages, of almost the whole of nineteenth-century British-controlled India (modern Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and parts of Myanmar). Sten Konow was the main editor of several LSI volumes, amounting to approximately one third of the whole, although only Grierson's name appears on the work as a whole: “[Konow’s] contributions were:—Vol. III, Parts i, ii (a portion), and iii (Tibeto-Burman languages), Vol. IV (Dravidian and Muṇḍā languages), Vol. VII (Marāṭhī), most of Vol. IX, Part iii (Bhīl languages), and Vol. XI (Gipsy languages.)” (LSI V1P1: 199fn)

For each major variety LSI provides (1) a grammar sketch (including a description of the sound system); (2) a core word list; and (3) text specimens (including a morpheme-glossed translation of the Parable of the Prodigal Son). The LSI grammar sketches provide basic grammatical information about the languages in a fairly standardized format. The focus is on the sound system and the morphology, but there is also some syntactic information to be found in them.

The language data for the LSI were collected around 1900, hence obviously reflecting the state of these languages of over a century ago. However, we know that both most grammatical characteristics (in particular inflectional morphology) and the core vocabulary of a language are quite slow to change, and sampling information from LSI shows that while some of the lexical items are not used today in everyday speech, most other information is still valid for the modern languages.

The LSI grammar sketches range in length from less than a page to over eighty pages, and the whole LSI comprises far too much text for it to be a realistic option to work with it manually in a systematic fashion. There is a digital version of the LSI available online through the University of Chicago’s Digital South Asia Library. However, this version is not searchable in any way (and text cannot be marked and copied), but simply presents an online book-reading interface, much like that of Google Books.

Digital resources based on the LSI

One important aim of our project has been to turn the linguistic data found in LSI into a structured linguistic database which we hope will be useful for many different kinds of linguistic investigation.

Most of the LSI has been digitized in our project (four of the books still remain to be processed), by double keying, a high-accuracy text digitization method. Our work has so far generated three kinds of digital resources based on the content of the LSI:

(1) The digitized text of the LSI in linguistically enriched format, providing access to the full text of the LSI, through

(1a) feature-rich online search: <https://spraakbanken.gu.se/korp/?mode=lsi>

(1b) download in a programming-friendly corpus format: <https://spraakbanken.gu.se/en/resources/lsi>

(2) Two interactive databases of linguistic features

(2a) 11 linguistic features in 267 South Asian languages visualized through an interactive map interface developed in our project: <http://demo.spraakdata.gu.se/lsi/maps/htmlMapsCV/maps-cv.php>

(2b) 72 linguistic features in 240 South Asian languages visualized through the interactive CLLD interface: <https://spraakbanken.gu.se/lsi/clld/>

(3) Comparative vocabulary (167 vocabulary items – single words and short phrases – in 292 language varieties) from LSI V1P2. This dataset is being prepared and will be made available for download.

The focus in this blog post is on the linguistic data resources produced in our project, and online interfaces for browsing and searching these resources. The project has also resulted in a linguistic framenet and a frame-semantic parser for processing free-text language descriptions in English, which are not presented here.

The LSI “corpus” comprises about 1.2 million words and consists of the full text of the digitized LSI volumes (excluding tabular data, such as vocabulary lists and inflection tables). It contains information about around 550 linguistic varieties.

As a point of entry to this dataset, we have reused a mature linguistic corpus interface, Korp (Borin et al. 2012), a versatile open-source corpus infrastructure which has been developed and maintained by Språkbanken Text for over a decade. Korp is a modular system with three main components: a (server-side) back-end, a (web-interface) front-end, and a configurable corpus import and export pipeline. The front-end provides options to search at simple, extended, and advanced levels in addition to providing a comparison facility between different search results, as well as various visualization options.

When importing the LSI texts into Korp, we have added lexical and syntactic annotations to the text, using the English Stanford dependency parser. We have added the following word and text level annotations to the LSI data:

- Word-level annotations: lemma, part of speech (POS), named-entity information, normalized word-form, dependency relation

- Text-level annotations: LSI volume/part number, language family, language name, ISO 639-3 language code, longitude, latitude, LSI classification, Ethnologue classification, Glottolog classification, page number, page source URL

The normalized word form is the form produced by removing the diacritics and replacing phonetic characters with their closest English-alphabet counterpart. The purpose is to make it easy to search the corpus, since the LSI consistently renders language names and glosses in a kind of phonetic transcription which will most likely be unfamiliar to many users, as well as hard to enter using a standard national keyboard. Thus, the normalization allows the user to search for, e.g., Bihārı̄ using the search string “Bihari”, or “bihari” (with case-sensitivity disabled).

The text-level annotations mostly represent the metadata which were collected from different sources in addition to the LSI volumes themselves, and are maintained as part of the corpus. The page source URL, for example, is a link to the corresponding page image in University of Chicago’s Digital South Asia Library, thereby complementing the latter resource which does not offer a text search feature.

Accessing the full text of the LSI

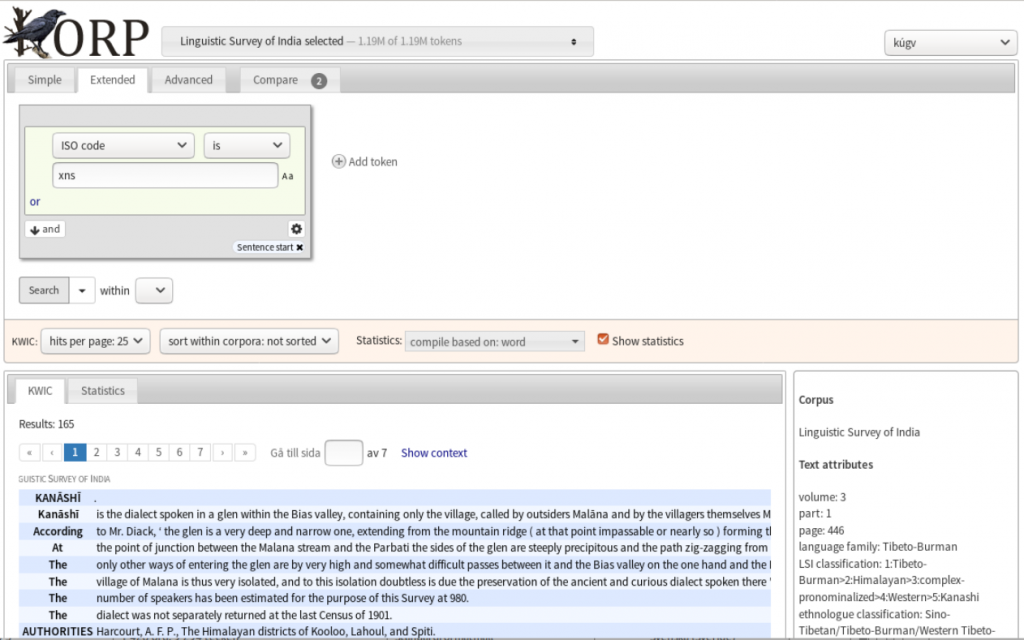

The Korp interface can be used for simple text search, as in the following figure, where the grammar sketch for the Tibeto-Burman language Kanashi (ISO 639-3 xns) is shown in Korp’s KWIC (Key Word In Context) view.

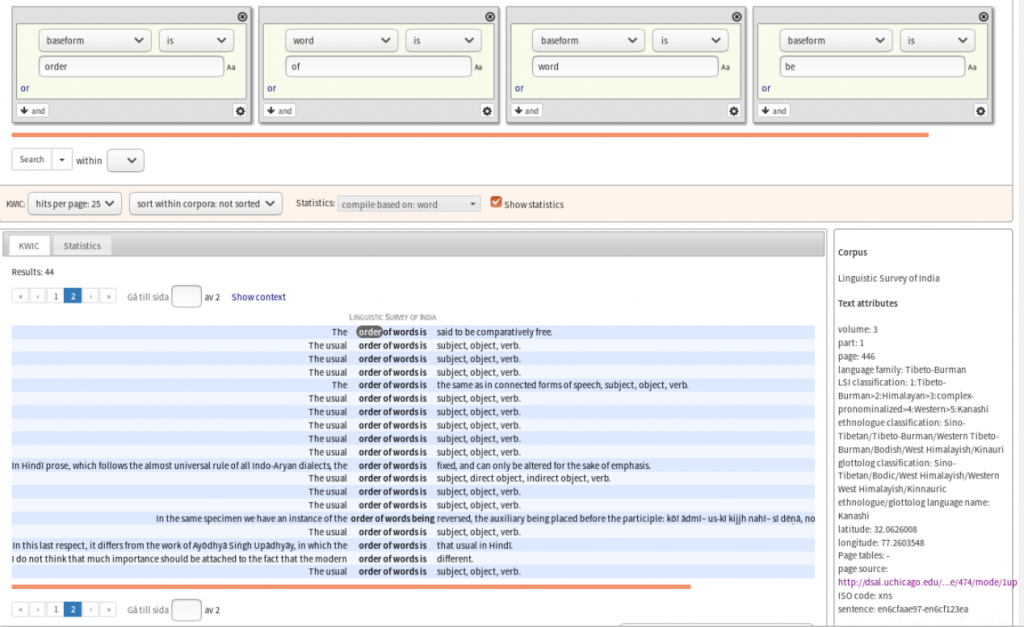

However, the real power of Korp lies elsewhere, since all annotations and metadata can be used as the basis for quite complex queries. The following figure shows the results of an extended corpus query for the four-word sequence order (lemma) – of (word form) – word (lemma) – be (lemma). This returns both “order of words is” and “order of words being”. The box to the right of the KWIC sentences shows annotations (word and text level attributes) and metadata for the highlighted word.

Map interfaces to linguistic features of the LSI languages

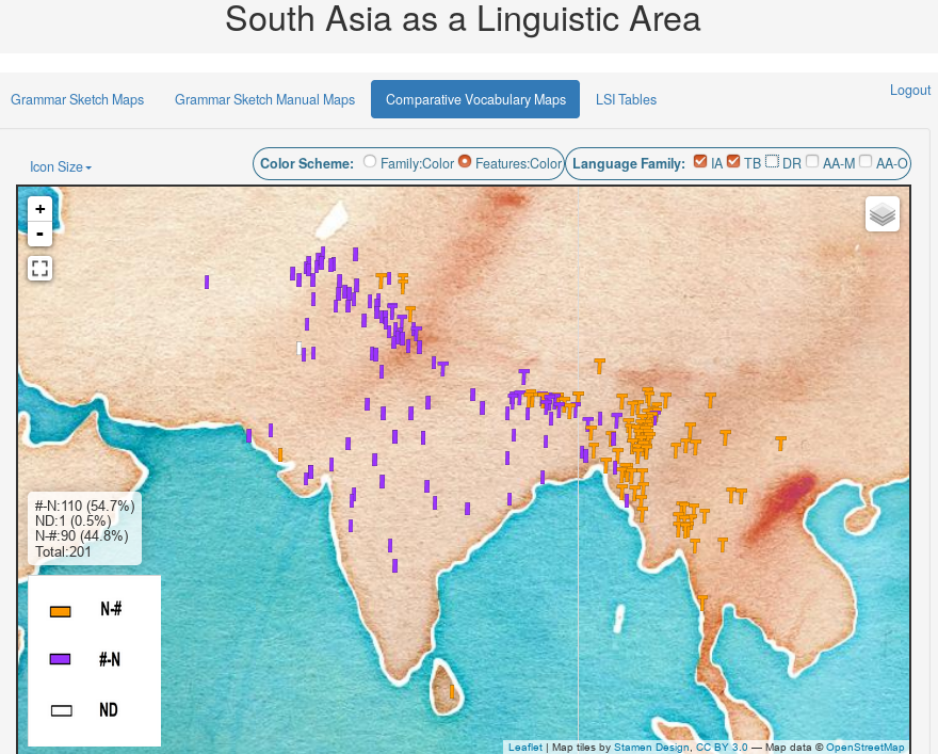

First, we show our own map interface (for 11 linguistic features in 267 language varieties). In this example, the position of numerals in relation to nouns in Indo-Aryan (I-shaped markers) and Tibeto-Burman (T-shaped markers) is illustrated: purple markers correspond to numeral–noun order and yellow markers reflect the opposite order. We see that there seem to be both genealogical and areal factors at play here.

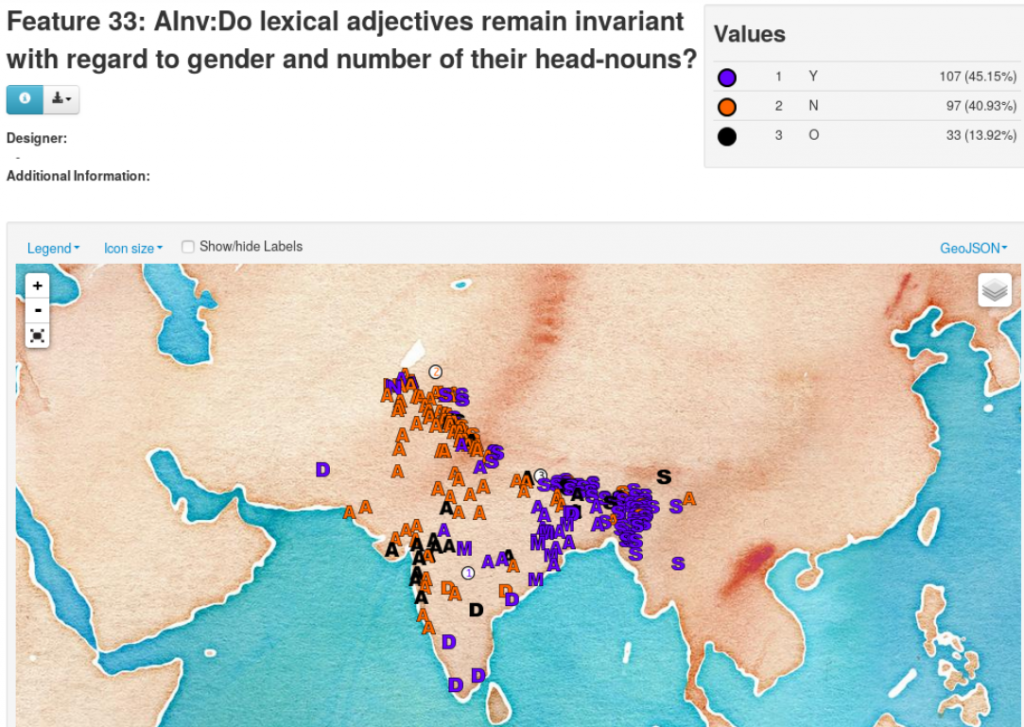

Second, the CLLD interface is a piece of open-source software developed and maintained by the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, and used in a number of websites exposing comparative language data (see <https://clld.org/>). In our CLLD instance, we use the mapping function available in CLLD to visualize the distribution of linguistic features over languages in South Asia. While most of the linguistic data visulized in our interfaces come from the LSI, in some cases we have also used other sources. The source information is available in the database. The example below shows the distribution of adjective agreement among South Asian languages, where we see a fairly clear east–west divide (language family legends in the figure are “A”: Indo-Aryan; “D”: Dravidian; “M”: Munda; “S”: Sino-Tibetan [= Tibeto-Burman]; circled number: language isolate).

In both these interactive mapping interfaces we can choose a language family (or more than one family) together with one or more linguistic features and display the geographical distribution of the combination.

These simple examples hopefully serve to illustrate the added value that digital language data and computational tools can bring to large-scale research on the world’s linguistic diversity.

Citing the datasets:

When presenting research using any of these datasets in a publication, in addition to naming the dataset itself, please cite the following publication:

Lars Borin, Anju Saxena, Bernard Comrie, and Shafqat Mumtaz Virk. Forthcoming. A bird’s-eye view on South Asian languages through LSI: Areal or genetic relationships? Journal of South Asian Languages and Linguistics. Forthcoming in 2020.

References

Borin, Lars, Markus Forsberg and Johan Roxendal. 2012. Korp – the corpus infrastructure of Språkbanken. Proceedings of LREC 2012. Istanbul: ELRA. 474–478. <http://www.lrec-conf.org/proceedings/lrec2012/pdf/248_Paper.pdf>

Grierson, George A. 1903–1927. A Linguistic Survey of India, vol. I–XI. Calcutta: Government of India, Central Publication Branch.