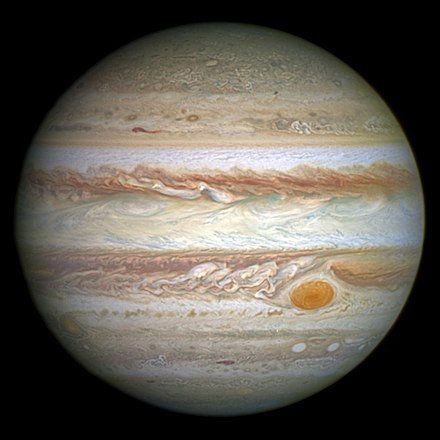

Those of you who are interested in astronomy may have noticed that you can currently see Jupiter in the night sky. Jupiter is in opposition (with the sun) – in other words, it's on the opposite side of us from the sun. That makes it easier to see, for a couple of reasons. First, it means that it's visible during the periods when we face away from the sun (that is, at night). Second, it means that the side of the planet we're seeing is the one facing the sun, so it's lit up. Specifically, the opposition happened around midnight between August 19 and 20, but Jupiter should still be visible for a few more days before descending for another year.

On top of that, since Earth and Jupiter are on the same side of the sun, opposition means that we are closer than usual. The point where something is closest to Earth is called perigee, although the word is most typically used about things that actually revolve around the Earth. The perigee of Jupiter, if we may call it that, technically happened about five hours after the opposition.

|

| Jupiter. Pictures are from Wikimedia commons unless graphs. |

This also means, quite obviously, that Earth is in its closest point to Jupiter, for which there is a specific word: perijove. A rare and beautiful word! It is used once in the book 2001 – A Space Odyssey. (Words that only appears once in a text are called hapax legomena, a term mentioned in a lot of books on corpus linguistics, but in many cases only once.) Personally, I've been trying to encourage its use as a metaphor – "proximity to greatness". As in: "Larry tried to keep it together after the divorce from Elizabeth Taylor, but he was never the same after leaving perijove."

So, apart from meandering segues about dated sci-fi books (pun absolutely intended), you're probably asking yourself, how can we bring language data into this? Can we perhaps learn something about astronomy by studying word frequencies? But of course!

|

| Halley (not the comet). |

In 1705, Edmond Halley noticed that a lot of people had talked about seeing comets in both 1531, 1607, and 1682, and realised that they must have been the same comet, returning every 76 years. Thus, the comet that bears his name was discovered, and Newton was proven right, using corpus linguistics! Sort of!

Okay, technically, he first used calculus and Newtonian physics to determine the orbit of the 1682 comet, and then realised that it must have been the same comet as those mentioned previously. But still!

So let's try applying the same idea to Jupiter. Can we verify the period of Jupiter by looking at how often it's mentioned online?

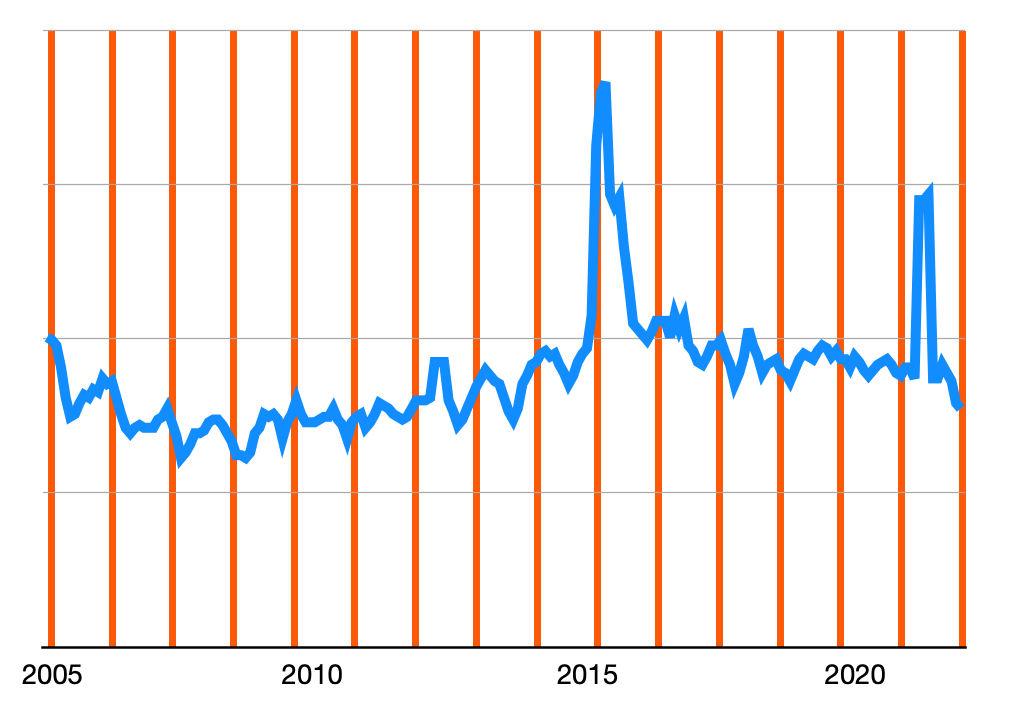

|

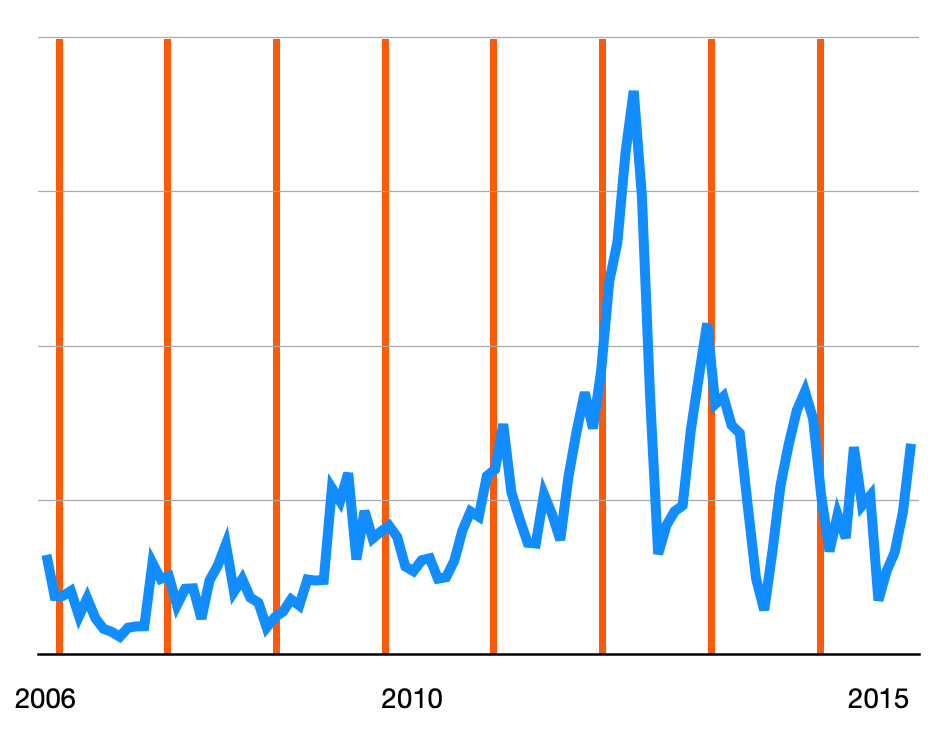

| The blue curve shows frequency of the word "Jupiter". The orange lines mark the dates of opposition. Data from Google Trends. |

First, we'll give it a try using Google Trends, which gives us statistics about what people search for. The first figure shows the frequency of mentions of Jupiter, compared with the times when Jupiter was in opposition. You can... kind of see a pattern? If you try really hard?

Analysing the numbers, we find that in the three months around the oppositions, the word is mentioned 4% more often. Success! Except... There's something going on there in 2015. Did people just really get into astronomy that year? No, to our disappointment, that is of course the release of the film Jupiter Ascending, which happened (?) to fall on the very same day as the opposition that year. So that might have slightly thrown off our data.

Jupiter, and the planets further from the sun, have periods of rotation around the sun which are much longer than a year (for Jupiter, 12 years), so that means that opposition happens just under once per year, when the Earth "catches up" to them.

|

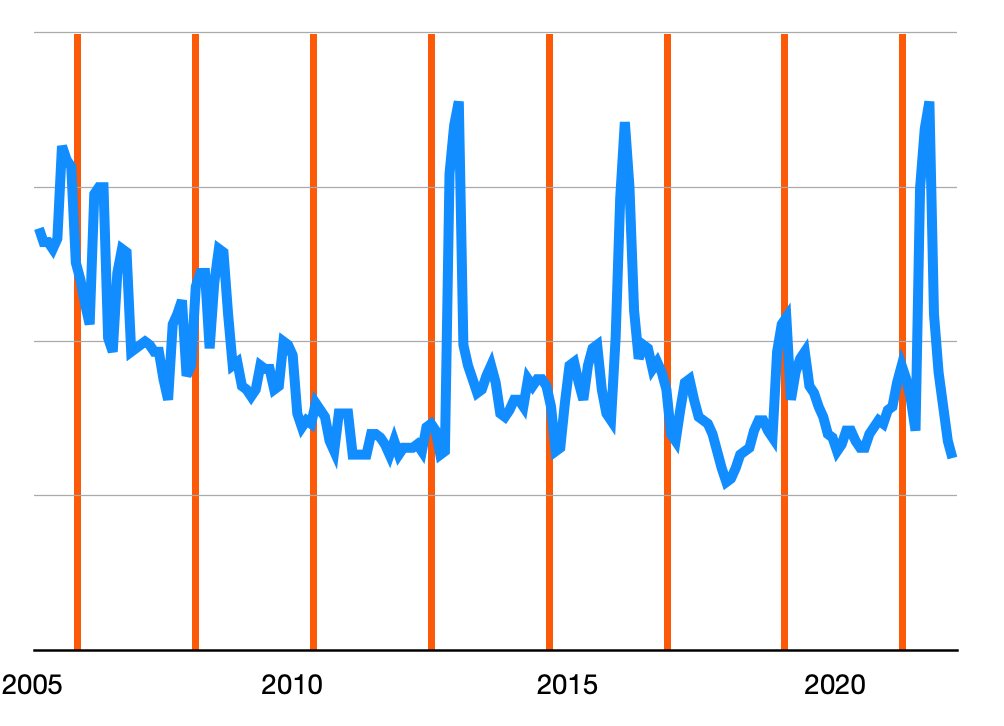

| Data for Mars, from Google Trends. |

The planets closer to the sun than us can of course never be in opposition – they are always in roughly the direction of the sun, seen from us. That leaves Mars, whose period of rotation is roughly two Earth years, which means that the time between oppositions is also about two years. In the second figure, we see the same thing as before, but for Mars. Again, it's... not overly clear. But it turns out the word is mentioned 3% more near the oppositions. Success again!

What if we look at social media? We try applying the same logic to our "Twittermix" corpus, using Korp. The results are in the third figure. The data here ends just before Jupiter Ascending came out, so hopefully we've eliminated that source of error. There does seem to be a curious peak in early 2012, for which I have no explanation. But is the word used more often near the oppositions? Yes, 7% more! Granted, this is not a particularly rigorous statistical analysis, but maybe good enough for blog purposes.

|

| Data for Jupiter, from Korp, using the corpus Twittermix. |

While we're on the topic of planets, their names are also quite interesting to a linguist. You probably know that they are named after Roman gods, but... what are the gods named after?

Mars is thought to be named after a god from some other people in Italy. Being the god of war, he has given us words like martial, and most likely a few modern names, like Martin and Marcus. Venus has more or less the opposite story, where the concept gave name to the deity – the word venus means "love", and seems to be related to venerable, venison, win, wish, and a few other words. In Nordic mythology, we have Vanadis, another name for Freya, the closest equivalent of Venus. There is also the family of gods called the Vanir, which might also be related.

Uranus is a bit of a special case, since he's not really a proper Roman god. The name is based on the Greek Ouranos, who didn't have as obvious a Roman counterpart as some of the others. Since Saturn was the father of Jupiter, it was considered appropriate that the next planet be named after the father of Saturn, which in Greek mythology was Uranus.

|

| Tuesday, probably. |

What about Jupiter himself? That name goes all the way back to the Proto-Indo-European mythology – the ancestor of both the Greek, Roman, Nordic, Hindu, and many other religions. Dyeus was the top god, the ruler of the skies – the name means something like "daylight". Since he was the father-figure of the gods, he was often called "father Dyeus", or Dyeus pater, which turned into "Jupiter". Dyeus is also the origin of the Greek version of Jupiter, Zeus, and it has a long list of relatives in English: deity, divine, dismal, lent, journey... The word Tuesday comes from the Germanic god Tiwas (or in the Nordic version, Tyr); it was a "translation" of dies Martis, "the day of Mars", since Tyr was seen as the Germanic equivalent of Mars, but the name Tyr seems to be derived from Dyeus, just like Jupiter... The various Indo-European religions did shuffle their gods around a bit, so these things can get confusing.

The Latin word for "day", dies, is also from the same origin as dyeus. Does the word "day" share that origin? They do look similar – seems plausible, right? Etymologists, ever the killjoys, tell us that this is probably not the case. But even so, we could make the case that since Tues- actually means "day", Tuesday arguably means "day-day". The sunrise of the week, after the darkness of Monday.

Makes perfect sense.