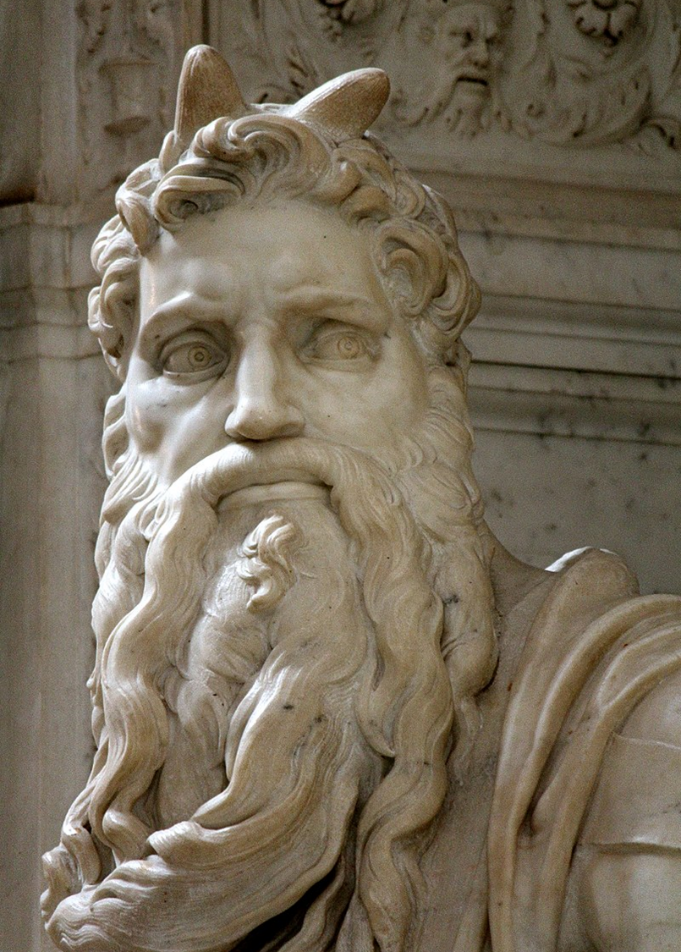

Here is Michelangelo’s depiction of Moses, a marble statue commissioned by Julius II. In it, we can see that Moses has horns.

But why does Moses have horns?

San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome

1513-1515, source Wikipedia

Most likely, the reason Moses has horns stems from a translation error of an ancient Hebrew word קָרַן (qāran) that should haven been translated into shining or emitting rays but that was wrongly translated to with horns. This is a concrete example of the fact that if we cannot understand our language correctly, we cannot understand our world correctly. And two important reasons why we cannot understand all language is that 1) people use the same words in differently ways, and 2) they used them differently over time, to keep up with our society and the world around us.

In the RJ-funded program Change is Key!, we will develop tools to turn text into a story of our language, our societies, and our cultures, and how these have changed over time. The program spans six years (2022-2027) and has 11 participating researchers and one research engineer. The program is split into three main areas,

(1) Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Language Technology (LT);

(2) computational modeling of language for historical linguistics and lexicography; and

(3) Humanities and Social Science (HSS) research questions that can be tackled with the help of computational modeling of (lexical and semantic) language change.

Our HSS research questions stem from analytical sociology, gender studies, and literary studies. Our researchers stem from six participating universities, IMS Stuttgart, Queen Mary University of London, University of Lund, Institute for Analytical Sociology (IAS) Linköping University, KU Leuven, led by the University of Gothenburg.

If change is key, then what is it that we mean when we talk about change? We refer to two main classes of change, diachronic and synchronic change.

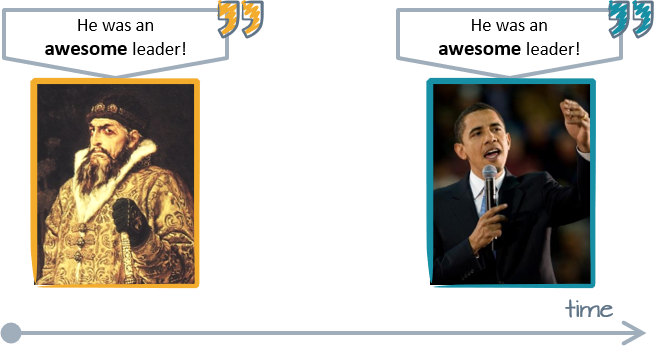

Diachronic change, concerns change over time: here the main kind of change is semantic change because it is devious. The same word that behaves different over different points in time. If the sentence He was an awesome leader is read today, it is interpreted as something positive. The word awesome refers to a cool, interesting, exciting, moving leader. However, in the past, awesome would mean someone who would chops peoples heads off, or at the very least, someone to inspire awe.

So the same word, but radically different interpretations over time. This does not have to be related to historical data, it can also occur in modern data, like surfing.

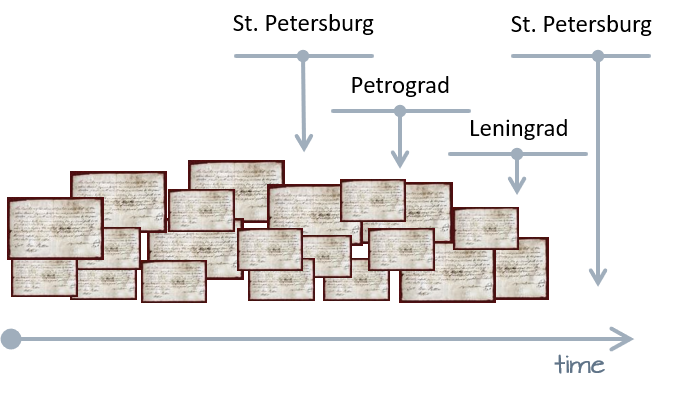

We also consider words that replace each other for the same meaning. For example, the city of St Petersburg is the same city, but has had many different names over the years, like Petrograd, Leningrad, and again St Petersburg.

Synchronic change takes place over different context and relates to linguistic variation. We consider all living and current versions of a word’s meaning. These are not necessarily the variations that you would find in a dictionary, but those you would find if you speak to people who are different from you; if you talk to young people, or really old people, those with higher education or differently educated than you, or those that have no education. So, across all different dimensions that form our society we find different usages of our language.

Often times, all three of these change types interact and form complex stories of our languages. In common for all three change types is computational representation of meaning.

Main CHALLENGES for computational models of meaning and change

Models to handle languages with smaller amounts of data

Current computational models of meaning and change are lacking in a few aspects. Firstly, they are bad at handling smaller amounts of data. The majority of our models are developed and tested for the English language. However, there are huge amounts of resources available for the English language. For example, GPT-3, was trained on over 45 terabytes of compressed plaintext before filtering and 570GB after filtering. Even if we were to digitize all Swedish texts, the upper limit (in terms of size) for subsequent corpora is expected to be between 2−5 TB, depending on the possibilities to transcribe spoken Swedish present in the Swedish National Library collections [efn_note]Sahlgren, Magnus, et al. "It’s Basically the Same Language Anyway: the Case for a Nordic Language Model." Proceedings of the 23rd Nordic Conference on Computational Linguistics (NoDaLiDa). 2021.[/efn_note]

And by the time we are done digitizing the Swedish data, there will be even more text available for English. This means, we cannot catch up, and we should not expect to catch up. Instead, we need to develop smarter ways of utilizing the data that we have. And if we are able to do so for Swedish, then many other languages that have less data can benefit from our efforts. Of course, this goes both ways and we benefit from efforts in other, lower-resources languages.

Models to differentiate between senses

The second main challenge that we have is that most models do not differentiate between a word’s senses. However, most of our words have more than one sense (meaning). For example, the word plane has one flat surface in space sense, and one airplane sense (in fact it has many more senses). In most datasets that we have, the airplane sense is widely dominating. However, many of our use cases need to (a) find the smaller senses (that is model them from the available data), and (b) find change in the smaller senses.

Models to tell us the what, how and when

Finally, almost all of the existing methods can tell us that something changed in the meaning of a word, but not what changed, how it changed or when it changed. This information is, however, crucial for many of our research questions and applications.

That is why, at the core of this program is to develop good computational models of meaning and meaning change. And this cannot be done by only computational (NLP/LT) researchers, because meaning to linguist is not the same as to a lexicographer, or to researchers from different humanities and social sciences. We need each other to be able to produce the good models that can answer our research questions.

Language Technology + Humanities and Social Sciences = ❤

To further strengthen the ties between language technology and humanities and social sciences, we have five different focus areas in the program. These focus areas concern research questions outside of the computational field that will be targeted within this program. The first two, historical linguistics and lexicography, relate to meaning change on a language level. The remaining three are research questions on a societal level, because societal change can be studied with extended methods for language change. In all of these, researchers from the respective area and computational researchers meet and research together over the course of the program.

Language level change. Our first focus area is historical linguistics where we will re-evaluate existing, mainly manually devised hypotheses of change on larger-scale data, modern data, and across many more languages. We will test existing classifications of change to see if they hold for modern text or if they need to be revised.

Our second focus area is lexicography. We will use computational modeling of semantic change to turn lexicography away from a methodology that is highly dependent on the lexicographer’s own interests, chance encounters, and certain difficult parts of the vocabulary that get revisited over and over again, to a methodology that continuously monitors modern language to find changes in a much larger part of the vocabulary. We will collaborate with the lexicographic unit at the University of Gothenburg who are responsible for the production of The Contemporary Dictionary of the Swedish Academy to ensure that our work is useful in the everyday work of lexicographers.

Societal level change: When it comes to analytical sociology, we will study radicalization processes to be able to interfere at an early stage. We will also study what drives attitudes towards different migrant groups and take a step towards devising better integration strategies.

Our research question from gender studies relates to how language and equality interact. We want to answer the question if policy makers and authorities use language to achieve equality in society. We will complement current manual and interview-based studies with larger-scale studies over larger populations, and longer time spans.

Finally, when it comes to literary studies, we will study which aspects of our lives that were affected by the introduction of modern technologies, like electricity or the steam engine. We can go beyond the obvious to the more abstract parts of our lives, and study how technological and societal change was problematized in literature as well as how they changed our aesthetic expression.

Our societal contribution. We want to make text interpretable for everyone, that means to resolve ambiguity that is present in the text on the basis of change, regardless if the text is historical or modern.

If you are a scholar and you want to research something of interest to you, for example how people’s attitudes towards vaccines have changed from their invention to now, you should not have to be an expert in the language it is written in. Nor should you have to spend all your time trying to understand the language in the texts you are reading. You should be able to find the content you are interested in, and interpret it. We will develop methodology for highlighting words in a text that are likely subject to a different interpretation in the text that what is the most likely current interpretation. And for computer-based analysis, we will automatically resolve the ambiguity to allow computational analysis of the text. For example, if you want to study how much happiness people have expressed in the past, you should be able to automatically find the different words used for expressing happiness for different periods of time.

This exciting research program will start with a bang in 2022! Be on the lookout for more information at the Change is Key! website!